Echoes of the Barroom Find Life in the Post Office

Under flickering neon’s jaundiced eye,

ghosts gather to watch the living collide.

Names change, fathers vanish, and new kinship’s a riddle,

But thunder always finds the cracks in the middle.”

~A Fanciful Poem by the Clown

The letter had come general delivery, postmarked Lakota, North Dakota. It was addressed to Johnny Antelope Ears. Mandaree’s postmistress, always snooping for news from the outside world, felt a prickle in her fingers as she steamed open the letter. The Clown sent a flash of lightning across the sky as her lips started to move over the words.

March 4, 1959

Dear Mr. Antelope,

I hope you don’t mind me trying to find you. I know that Elbowoods doesn’t exist no more and I’m guessing you might live in Mandaree. How are you doing? I wonder about life on the reservation and think it must be tough. I don’t think it’s much better here.

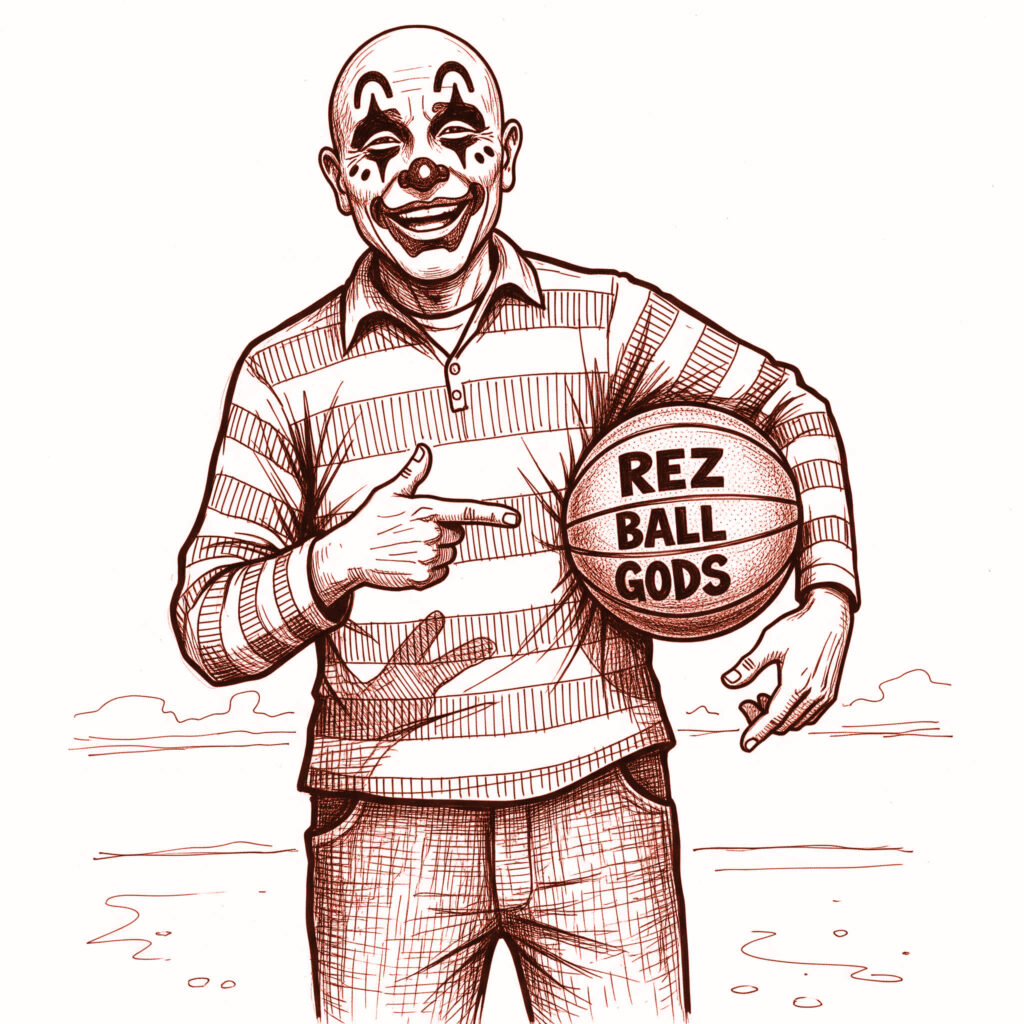

I was just listening to the state tournament and realized that it’s been seventeen years since we were young, and we were on opposite teams in the North Dakota basketball championship. Do you remember me? You didn’t play and I never should have. I was way too old, but I was too chickenshit to say anything. I always admire you for telling the truth about your age and sitting out the championship. I didn’t have the courage to do what you did. Maybe I still don’t.

I always remember how we stared into each other’s eyes in the final seconds of that game and how weird that felt. It was strange for me, anyway. Like we were brothers or something.

I own a bar and lutefisk joint in Lakota. Came back home after the war and that was a mistake. Lots of name calling of Germans and Indians. I was wounded and hobble around some. How about you?

We got new missile bases around here to protect all Americans against the Russians. I hear there’s even nuclear missiles. Scary but those enlisted men sure like our girls and binge on our lutefisk. Beer helps, too.

At my mother’s funeral about ten years ago, a highway patrolman showed up and acted real sad like. He claimed to be my dad. My mother never married. He said that he had another son on Fort Berthold. Isn’t that funny? Do you know anything about a fat, sneaky highway patrolman?

I would like to meet you after all these years. Do you ever get to Minot? I could meet you and we could have a beer. I know you Indians can’t drink on the reservation. You could also come to Lakota, and I’d show you a good time. I don’t mind Indians at all. Please let me know if we can see each other after all these years.

Sincerely,

Eric Bimdahl

News of that letter stirred things up on Fort Berthold. The postmistress spread the gossip all over Mandaree. From there it traveled fast. The cheating White boy had admitted he was sorry! Why had his apology taken so long? Never mind. The juiciest part was that Eric Bimdahl was a bastard and there might be another bastard son of that same highway patrol man roaming around Fort Berthold. Whoever it was, he had to look at least a little White. Who was he? For the first time since the relocation from the Bottom Lands and the shame that brought everyone to the top, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara started to stare themselves directly in the eye, silently trying to figure out exactly who belonged where.

Johnny Antelope Ears understood right away. Of course, he had heard rumors but had never particularly cared. So, what if his eyes weren’t quite brown, his skin off hue, and his hair was tinged with red? Intertribal and non-tribal liaisons were a fact of life and had been common since Lewis and Clark, the steamboats, and maybe the Vikings before that. But the current hub bub was about his looks. The postmistress had resurfaced his basketball celebrity. Curiosity made him write Eric back.

March 15, 1959

Dear Mr. Bimdahl,

Of course, I remember you from 1942. You were a very good player. For a White guy! Just kidding.

The state B tournament was fun to hear on the radio, but the reception wasn’t good. Bottineau won with the help of them Chippewas boys from up on their rez. Fort Yates didn’t do as good with their Lakota and Dakota boys. That’s OK because them Sioux eat dogs. They also made our ancestor’s lives miserable. We still like them, though. Again, just kidding.

Life here is hard. There are no jobs, but the government talks about more work for our people. It was tough losing Elbowoods to the waters. I’ve been coaching basketball since returning from the war in Elbowoods and now up on the Top Lands. I was in the Pacific theatre and killed a lot of Japs and never got wounded. I’m sad I killed all those Japs.

Interesting about that highway patrol guy. Did you catch his name? My relatives said there were several down this way in the 1920’s but the roads were really rough so sometimes they had to pull over and spend the night. I don’t know where they slept.

I can meet you in Minot. I would like to stare into those eyes again and see what we can find out about the future. I will be there in the afternoon of May 1st if my car can make it. My cousins say that Filthy Lil’s is a good bar.

If you figure out that highway patrolman’s name, please write me back soon.

See you then,

Johnny

No one knew why Eric’s shut his bar down early on April 30. “I’ve got to get out of town for a little bit. You guys will be OK. I’ll leave some lutefisk on the back porch. Don’t make a mess of things. I’ll be back soon” he said to his regulars. In the morning, he gunned his Fairlane to Minot and uncharted ground. Back on Fort Berthold, Johnny steered his father’s 1934 Plymouth Six up toward New Town and on to Minot. This would be an interesting day.

They both arrived at Filthy Lil’s shortly after 1 p.m. They exchanged pleasantries in the same way that Odin and Only Man had been doing for eons. Staring into each other’s eyes the bar rotated several degrees. Out of Eric’s hand, a smudged birth certificate fluttered to the ground.

In the corner of the bar, drunker that the proverbial North Dakota skunk, a small voice proclaimed, “pick up your litter, you lazy twats.” It was Mamzer He She, filthy and displaced, out of work as a government lawyer and now keeping bones and skin together by part-time janitorial work at the local state teachers college.

Eric picked up his certificate and handed it to Johnny. “Let’s talk about that highway patrol guy. Looks like on his name was Olson. Charles Olson. My mom must have told the doctor that because I know he wasn’t anywhere to be found when I was born.”

“Olson? That’s funny. When we want to insult someone back on the Rez for acting all white and everything, we call them Olson. Don’t know where that started but even I’ve been called an Olson a time or two.”

The barroom was rotating faster now. Ignoring He She, Johnny and Eric walked uphill to the bar. “I haven’t felt like this since 1942,” Johnny said in a low voice. “Neither me,” Eric replied. A Gjallarhorn blasted. At exactly the same time, a Hidatsa drum underlaid a prophetic chorus, “Above the earth I walk, On the earth I walk.” The whole bar roiled. Neither Eric nor Johnny had yet had a beer, but they were nonetheless, and as they said on Fort Berthold, three tipis into the wind. They could barely make themselves heard in the din.

“Holy shit! Did you hear that Indian music?” Eric slurred.

“Yes, I did! Did you hear that plastic Viking horn?” Johnny hollered.

“You’re both crazier than two-peckered owls!” screamed He She, barely standing up in the middle of the undulating floorboards.

Outside thunder crashed, near Crow Flies High Butte the prairie flashed purple with lightning, and the time honored fistfight between Only Man and Odin started once more. Down in Bismarck, John Anderson sighed as he put an earmarked folder marked “For My Successor” in a filing cabinet in the back corner of the North Dakota State High School Activities Association office. He was retiring and soon would devote his remaining days to sport fishing in the waters behind the new dam. He was oblivious to the darkening skies to the north and the waves lapping up on the shores.

1964, Bloodlines in the Shadows

“When the gods are bored, they mix the blood and spill the beer—and call it heritage or mix them together and call it a miracle.” ~ The Clown

Johnny Antelope’s 1964 version of the Mandaree Warriors had done well on the basketball floor. Like red willows woven from the Bottomlands the team had come together as a competitive force in North Dakota basketball for three years running. The only dent was that two years earlier the Warriors were odds on favorites to win the State Class C basketball championship but lost the first game when hangovers kicked in. Several downtown bars in Jamestown that had been happy to serve any one with money the night before. Odin was pleased to find this chink in the Warrior’s armor. Johnny and his team up vowed to not let it happen again.

The lid was blown clear off the lard can when Eric Bimdahl’s postcard arrived a week before the state tournament. Eric had chosen his words thoughtfully, but such care wasn’t necessary. The postmistress made sure everyone getting their mail that day knew every word.

Dear Johnny,

Looks like us Olson brothers are doing great! You with your unbeaten Warriors and me with my bar here in Lakota. The ghosts of 1942, including this old ghost are rooting for you and your great team! Our dad is proud! Eric (Olson) Bimdahl

Rumors spread quick on the Rez. Did anyone still living remember a highway patrolman named Olson? Wasn’t he that freckled redhead who looked goofier than a fat orange coyote and was real friendly to everyone around Elbowoods? Never wrote up any tickets. Surely, he wouldn’t have fathered any babies on the reservation, would he? And, what about this Eric Bimdahl? Wasn’t he the one who cheated Elbowoods out of the 1942 championship by being old enough in that game to shave a beard? He’s Johnny’s half-brother? They’re both “Olsons?” What could this possibly mean for our basketball teams, our way of life, present and past? What about Johnny? How is he taking this?

Local clergy were asked for input. Father Aloysius Bittman, the weathered guardian of Saint Anthony’s Indian Mission between Mandaree and the risen waters, carried a reputation all his own. Legend had it that he singlehandedly dragged his Volkswagen Bug from the semi-frozen grip of the lake one March afternoon en route to a Whiteshield mass. The shortcut was his secret route, skirting the new shoreline, and his man handling of the half-sunk bug had made him a folk hero. Life Magazine seized on the tale; North Dakota’s quiet corners were suddenly national headlines.

A song composed about his valor the priest’s faithful overlooked one detail—Only Man had lent his invisible hands to the retrieval, only to be ignored in the song. Odin might have been lurking nearby hoping for a lyric or two, but gods don’t generally dally with Catholic clergy.

When pressed about the Olson brothers and their dubious legacy, the good Father’s response was measured, seasoned by years of delicate diplomacy: patience and forgiveness. The same soothing mantra he’d long dispensed when villagers asked how they might reclaim the 1942 championship trophy. “If trouble comes knocking,” he’d say with a weary smile, “just push it right back down.”

Johnny and Eric—now known if mostly to themselves as the Olson brothers—made their trek to Minot during the spring thaw. The journey had lost its edge and all its glamor; the old barroom lurched and spun its stories on the same looping reel. Familiar voices, the weight of kinship, the predictable swirl of memories.

On the screen, Odin flicked the winning shot in ’42. Outside, a red-headed highway patrolman laughed, chugging up frozen gravel near Lakota and Elbowoods. Purple skies painted an eternal fistfight between two weathered gods. The loop, flashed through their minds like lightning that they’d already seen.

The storm passed and the barroom settled down to monotony. Just beyond calm’s perimeter, a scratchy voice rose in volume. Mamzer had wormed his way into managing Filthy Lil’s. He barked, “Get off the floor! Up, you drunken bastards!” His fury shattered the hush.

“You pull this every other week, and it takes me days to clean up your mess. I’m a forgiving man—I am the genius who made North Dakota’s damn dam happen, don’t forget that! I’m a lawyer, not a babysitter for white trash and their loser friends!” His words rang with the cold authority of the North Dakota Bar Association, whose verdict on his misconduct had used similar language in yanking his law license,“Get the hell out of the bar!”